At 11:00 a.m. on the 11th of November (the 11th month of the year) in 1918, an armistice was signed which ended World War I. For many years after that, November 11 was celebrated as Armistice Day and then, as wars continued to pile up, became our national celebration of Veteran’s Day.

In 1918, after four hard years of war–“the war to end all wars” as it had been called–finally came to an end. On the website, “Eye Witness to History” the Armistice was described (in part) this way:

Colonel Thomas Gowenlock served as an intelligence officer in the American 1st Division. He was on the front line that morning and spoke of his experience a few years later:

On the morning of November 11 I sat in my dugout. . . . A signal corp officer entered and handed us the following message:

Official Radio from Paris – 6:01 a.m. Nov. 11, 1918

Marshall Foch to the Commander-in-Chief

1. Hostilities will be stopped on the entire front

at 11:00, November 11, (French hour).

2. The Allied troops will not go beyond the line reached at

that hour on that date until further orders.

There was great celebrating throughout France as the war came to an end.

As an aside, my genealogy buddy and cousin, Kevin, who has superior sleuthing skills, discovered that Nov. 24, 1918 had been declared “Father’s Day”–a holiday still in its infancy. As described by The Learning Channel (tlc) website:

In 1916, two years after he proclaimed May 9 as Mother’s Day, President Woodrow Wilson verbally approved Father’s Day, but he didn’t sign a proclamation for it. The closest the U.S. came to honoring fathers nationally during Wilson’s presidential tenure was a Nov. 24, 1918, letter-writing campaign between fathers on the home front and their sons deployed in Europe. The activity was suggested by Stars and Stripes, the official newspaper of the American Expeditionary Force in France. Since World War I ended two weeks before the letter campaign, the letters were delivered safely on both sides of the Atlantic.

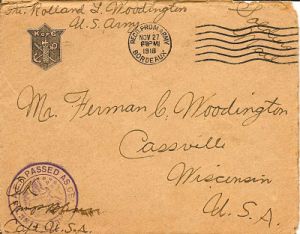

Private Rolland Woodington was serving in France when World War I ended. On November 24, he wrote to his father, Furman Woodington, as part of the Father’s Day letter-writing campaign, and described a bit of his life there:

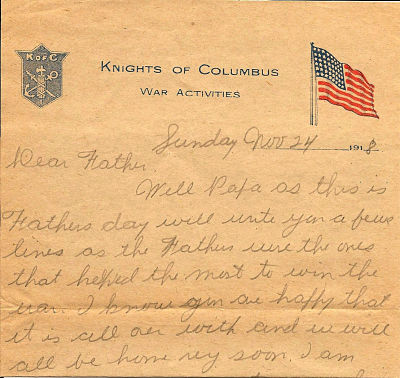

Sunday, Nov 24, 1918

Dear Father,

Well Papa as this is Fathers day will write you a few lines as the Fathers were the ones that helped the most to win the war. I know you are happy that it is all over with and we will all be home very soon. I am having a very nice time over here along with my work and when the war was going on we were all very busy although we hardly know the game is finished as our work still keeps going on. This is a wonderful country and a great many things to see and as I have got over a great deal of it in 5 months have seen quite a lot of interesting things. We had a grand time the night the war ended and the following Sunday I went to Bordeaux where there was a great deal of celebrating and everyone was very happy. I have charge of a warehouse with an ass’t and I have enough food in it to last a family a good many years. I like the work fine and all the rest of the fellows also. I haven’t seen my company since July but when I join them again I know where I will go that will be back in the good old States. A great many of the boys and girls over here lost their Fathers in this long war and I can be thankful to have mine. A person hardly realizes the horrors of the war in the States but here most every family in this country have lost someone of the family. I have seen enough to last me for some time to come. We had a very rainy day all Sunday but everyone was happy. What did you do to spend the day set aside for the Fathers? Hope you had a pleasant day and that you will spend many many more such days. I got a letter from Walter [Rolland’s brother] yesterday, glad he likes the army but I guess he will soon be out as the fellows in the States will be out much sooner. Just as soon as peace is signed the boys will come rolling back. We have some long trip ahead of us but we will know each day is getting closer to home. We don’t have hardly any sickness in our camp but we are in a fine climate. Hope this finds you all well and happy as this leaves me and that the next Fathers day we will all be together and have a good time. Have a good time Thanksgiving as we will over here. With lots of love to you all I am as ever your son,

Pri. Rolland L. Woodington

Detach 311th Supply Co.

Guest Author: O. Darrell Aderman

I don’t remember the exact summer, but it was just after World War II when a number of relatives from Illinois were up to visit. The whole Aderman family was down to the farm to meet them. It was a beautiful summer day until the middle of the afternoon when the sky in the west turned an ominous black. Grandpa Aderman (Carl) felt down in the dumps because he had that whole west field full of hay bales lying on the ground, a majority of his supply for the winter. My dad (Oscar) moved quickly and indicated that the storm was moving slowly. With all the help sitting around we could get most of it in before the rain got there.

The crew was divided and the larger tractor went out in the field where men and boys carried bales of hay to the wagon to be loaded. Meanwhile, the smaller tractor was attached to the elevator and made ready to run bales up in the hay mow. By then the first wagon came in to the elevator. It was a sight to behold: men on the wagon loading bales on the elevator, almost touching each other. Men in the haymow were standing in line to take bales off of the elevator and carry them back for storage: never letting one hit the floor of the mow. By that time another wagon was in with a load. This continued until every last bale was in the barn. It was less than five minutes before the rain came down with a vengeance.

It was a good feeling to all the relatives that helped. I remember Grandpa Aderman saying something like . . . “I just saw a miracle.”

On this day in 1930, Rolland Woodington died of a heart attack while he was driving in Chicago. Rolland “Raleigh” Woodington was the second child of Furman and Barbara “Dolly” (Sturmer) Woodington. He was born September 13, 1892 when his older sister, Ethel (my grandmother), was two years old. He was born in Cassville, WI and it was there he grew up with his sister and four younger brothers.

In 1910, according to the U.S. Census, Rolland had been in school in the previous year while still age 17. Sometime before he was 24 years old, Rolland “Raleigh” moved to Chicago and worked as a steward in the Briggs House Hotel on the corner of Randolph and Wells Streets. The Briggs House was one of the early hotels built in Chicago when it was still a small town. The hotel burned in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and was soon rebuilt. As a steward at the Briggs House, Raleigh’s work was likely that of what is also known as a maitre d’. Stewards were responsible for the dining experience of the hotel guests, overseeing all of the details and hospitality except for the actual cooking in the kitchen.

On June 5, 1917 Raleigh fulfilled his legal responsibility to register with the 17 Ward 6 Draft Board in Chicago, IL. He served in World War I (as did his younger brother, Walter, according to http://www.cassville.org/Veteransalute.html). He had an interesting incident about six months after he had registered for the draft. There was a recommendation by the Bureau of Investigation (now called the FBI) that he be investigated for his loyalty to the United States and it be determined whether he had registered for the draft:

After returning from the war, Raleigh moved back to Chicago and worked as a soap salesman. He married Claudine Ceryle on March 24, 1920 but they later divorced, a detail found in his death certificate.

World War I veterans often suffered from what was then called “shell shock”–now called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Whether it was from shell shock or some other reason, the family suspected Raleigh, like many veterans, had resorted to drug abuse after returning from the war. Rolland died October 26, 1930 at the age of 38 from a heart attack while he was driving. The cause of death, according to family stories, was either a drug overdose or a weakened heart from when he got the flu during the Influenza Epidemic of 1918 while in the military. He was buried in Cassville, WI on Oct 29, 1930.

Note that both his name and age are incorrect in the newspaper obituary, but the date of death and address are correct according to his death certificate. My thanks to cousin Lori Hahn for finding his obituary.

John Sturmer was born in Filzen, Germany on March 25, 1820 and immigrated to the United States in 1847 with two of his brothers and two sisters. (I wrote earlier about one of his brothers, Peter, who went to California during the gold rush and was killed for his gold as he was returning home.) John stayed in New York state for two years before moving to Galena, IL. There he married Barbara Barton, another recent immigrant. Soon after, they moved to Grant County, Wisconsin where they lived the rest of their lives.

Today we remember the anniversary of his naturalization as a U.S. citizen on October 23, 1856 in Lancaster, Grant County, Wisconsin.

- A copy of John Sturmer’s naturalization certificate.

It reads:

“John Sturmer, a native of Prussia aged 35 years, a free white person makes report of himself for Naturalization and declares an oath that it is bona fide his intention to become a citizen of the United States of America, and to renounce forever all Allegiance and Fidelity to every Foreign Prince, Potentate, State, or Sovereignty whatsoever, and more particularly such allegiance as he may owe to the King of Prussia of whom he is at present a subject.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and affixed the seal of the said Circuit Court, at Lancaster in said County, this 23rd day of October, A.D. 1856.

[signed] John G. Clark, Clerk

On Monday, October 9, 1944, Furman Woodington celebrated his 84th birthday. The following Sunday, his daughter, Ethel (“Mrs. Monroe Hope” in the article below, my grandmother), hosted a birthday celebration for him. The local newspaper wrote the following article:

OLDEST IN TOWN HAS BIRTHDAY

Furman C. Woodington of Cassville is 84

Cassville, Wis. — Special: Cassville’s oldest native citizen, Furman Clarke Woodington observed his 84th birthday this week, and Sunday was honored at a dinner given by his daughter, Mrs. Monroe Hope, with whom he makes his home.

Mr. Woodington was born in Cassville, Oct. 9, [1860], and in his youth was employed as a stone mason apprentice. He also worked on the Canadian Pacific railroad and on steamboats which rafted logs down the Mississippi river.

He was custodian of the Cassville public school for 27 years, during which time his six children went through grade and high school. At the same time he served as mail messenger.

His wife, the former Dollie Sturmer, died in 1937. His children are Mrs. Hope, Cassville; Jennings Woodington, Deerfield, Wis.; Walter Woodington, Bagley, Wis.; Marc Woodington, Chicago, Ill.; and Robert Woodington, Rock Island, Ill. Another son, Rolland, who served overseas in World War I, died in 1930.

Mr. Woodington retired from active duty about 12 years ago, due to injuries received in a fall from a ladder. He enjoys good health and makes daily trips to town.

The Survivors Move Forward

Part 4 briefly described how the larger Donner Party got split into three groups–the Donner family at Alder Creek, the other families at Donner Lake, and the group that set off on snowshoes to get help. Three relief parties were sent up to get the survivors and bring them to California.

Of our distant Blue family ancestors, here is a synopsis of their fate: (the basic information is found on the website of the Blue Family Foundation, Sixth Generation; scroll down to section 6AL.)

Mary Blue is thought to have died before the trip because George Donner had married a third time to Tamzene Dozier. George died in the mountains, in part due to his wounded hand, and Tamzene was last seen sitting with him as he died in their makeshift tent. The daughters of Mary Blue and George Donner, Elitha Cumi Donner and Leanna Charity Donner survived and ended up as orphans in California. They were taken in by a couple but left that home as soon as they were old enough.

Elitha (1832 – 1923) married one of her rescuers, Perry McCoon, in 1847, later in the same year they had been rescued. Perry died in 1851 as a result of a horseback riding accident. She then married Benjamin Wilder. In her adult life, she spent much time speaking to the conditions of the winter tragedy and denying there was any cannibalism involved.

Leanna (1834 -1930) married John Mattias App.

Elizabeth Blue, married Jacob Donner. Her first husband, James Hook, abandoned the family so she had previously divorced him. Both Elizabeth and Jacob died in the mountains before they could be rescued.

Elizabeth had two children from her first marriage: Solomon and William Hook. Solomon (1832 – 1878) did survive the journey and later married Alice Roberts. He died young, though, in his 40s. William died (1834 – 1847) at the age of 12 or 13 as part of the Donner Party tragedy.

Elizabeth and Jacob had five children together. Their two oldest, George (1837 – 1874) and Mary (1839 – 1860) survived the journey although both of them died at young ages. Their younger siblings, Isaac (b. 1841), Samuel (b. 1843), and Lewis (b. 1844) all died sometime over the winter of 1846/1847 as a result of the horrible living conditions.

The story of the Donner Party looms large in the history of our country’s expansion west. It is filled with horrors and terrible difficulties, yet it also demonstrates an incredible resiliency of the survivors and the settlers who followed them.

In a previous post, the Donner group got caught in a terrible winter storm and had gotten separated into two groups. When the winter storm hit so fiercely, the 22 members of the Donner family and servants who had lagged behind because of the injury to George Donner’s hand, had to quickly build some makeshift shelters at Alder Creek with the quilts, tents, and buffalo robes they had with them, along with some brush they found in the woods. There were many children with them and several of them survived rather well during the months stranded in the snowy mountains.

The rest of the group forged forward to the east end of what is now called Donner Lake and did reach a cabin. They quickly built two more cabins and, as the winter wore on, built a few more small cabins to house the 59 people with them. In a short amount of time, they killed the last of their oxen for food and lost many of their other animals who had wandered off, died, and got buried under the heavy snowfalls.

After evaluating the situation, a group from the cabins made snowshoes from the branches they found and started out to find rescue help for the travelers. They struggled terribly in the rain, ice, and snow as they worked their way to Sutter’s Fort and quickly ran out of food. As they died one by one from malnutrition, that group also was compelled to resort to cannibalism. The group that left to find help was originally ten men and five women. All five women survived the journey but eight men died.

About three weeks after the “snowshoe party” arrived at Sutter’s Fort, in early February, the first rescue party left to help the stranded emmigrants. The conditions were so severe they were not able to bring in pack animals or wagons (and therefore enough food) and only a few people were able to be brought out at a time. Two more relief parties followed, but more of the helpless travelers died while waiting.

In the previous post, the ancestors of Floy Bates Aderman leading back to the American Revolutionary War were delineated. Here is the path from my maternal great-grandfather, Furman Woodington:

Furman Clarke Woodington (Oct. 9, 1860 – Feb 28, 1946) was the

son of Henrietta Munson Woodington (1843 – Sept 8, 1882), who was the

daughter of Amos Munson (1808 – August 5, 1885), who was the

son of Freeman Munson (1786 – Nov 1878), who was the

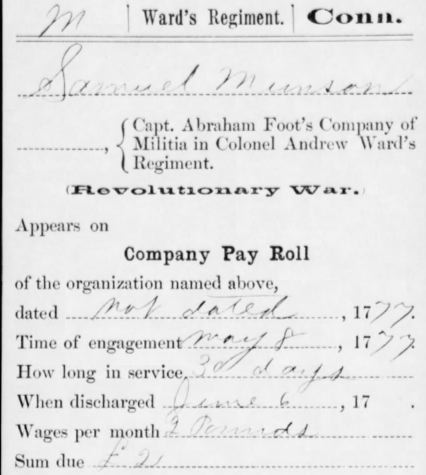

son of Samuel Munson (Oct 7, 1739 – April 2, 1827) who served in Captain Abraham Foot’s Company, Ward’s Regiment from Connecticut, led by Col. Andrew Ward:

According to the book, “Record of Service of Connecticut Men in the I. War of Revolution, II. Ward of 1812, III. Mexican War”:

This regiment was raised in Connecticut, on requisition of the Continental Congress, to serve for one year from May 14, 1776, and stood on the same footing as the other Continental regiments of 1776. It joined Washington’s army at New York in August, and was stationed at first near Ft. Lee. Marching with the troops to White Plains, and subsequently into New Jersey, it took part in the Battles of Trenton, Dec. 25, ’76, and Princeton, Jan. 3, ’77, and encamped with Washington at Morristown, N. J., until expiration of term. May, 1777.

Sometime after the war ended, Samuel moved to Trumball County, Ohio where he lived the rest of his life. He died April 2, 1827 at the age of 87.

I have known people over the years who were Daughters or Sons of the American Revolution. I understood that they could trace their ancestry to someone who fought for the freedom of this brand new nation and that was a very special honor. As I have been exploring military records the last several weeks, I have been able to confirm an ancestral path to the Revolutionary War through both paternal and maternal lines. Here is the paternal lineage beginning with my great-grandmother:

Floy Bates Aderman (Jan. 21, 1889 – Nov 1, 1960), who was the

daughter of Robert Josiah Bates (June 28, 1853 – May 18, 1926), who was the

son of Elizabeth Ann “Betsy” Blue (Oct 3, 1834 – June 23, 1874), who was the

daughter of Martha Blue (Jan 22, 1811 – Feb 11, 1868) and Robert Blue, Jr. (1811 – April 1884).

Martha Blue was the daughter of John Blue (Sept 9, 1777 – Oct 20, 1841);

Robert Blue, Jr. was the son of Robert Blue (1784 – 1840).

John and Robert were brothers and the sons of John S. Blue (May 27, 1750 – July 13, 1833).

John S. Blue entered the Continental Army on August 2, 1777 in Elizabeth Town, Lancaster County, PA. He fought in the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777 (with Gen. George Washington as his highest ranking officer) where he was wounded in the head by a sword. He was captured that day and was a prisoner of war until June 14, 1778. He was then discharged two days later. Fold 3 has his Revolutionary War Pension information online; following is the most legible letter, typed in 1929 to a family genealogist confirming his experience:

As an aside, after the war, one of John Blue’s friends from Pennsylvania applied for a war pension and needed witnesses to vouch for his character and identity. Among the signatures was John Blue.

John moved from Pennsylvania to Kentucky some years after the war, then to Ohio. His last move was to Indiana and that is where he is buried. (See Blue Family Genealogy, 1.1.3.2 for details. Please note: this is not Captain John Blue, 1.1.1.1)

Today, June 18, 2012, is the Bicentennial anniversary of the start of the War of 1812. Marking this moment in history, this is the second of two posts today. The first acknowledged Pvt. Freeman Munson, my 5th great-grandfather, who deserted after five months in the army.

The focus of this post is Major Uriah Blue (1.1.3.1.2 in Blue Family Genealogy), the first cousin of Floy Bates Aderman’s great-great grandfathers, Robert and John Blue. (Robert and John were brothers who married McNary sisters; Robert’s son, Robert Jr., married John’s daughter, Martha. Robert, Jr. and Martha are Floy’s great-grandparents.) Uriah Blue was a second Lt. in the Provisional Army of the United States in 1799, while still living in Virgina and worked his way up the ranks to Major. He distinguished himself during the War of 1812 and the Creek Wars.

According to the U.S. Army Historical Register, Uriah’s military service included:

Blue, Uriah. Va. Va. 2 lieutenant 8 infantry 12 July 1799; honorable discharged 15 June 1800; 2 lieutenant 2 infantry 16 Feb 1801; honorable discharged 1 June 1802; 1 lieutenant 7 infantry 3 May 1808; captain 9 May 1809; major 39 infantry 13 Mar 1814; honorable discharged 15 June 1815; reinstated 2 Dec 1815 as captain 8 infantry to rank from 9 May 1809 and with brevet of major from 13 Mar 1814; resigned 3 Dec 1816; [died – May 1836.]

Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army

B.

page 226

Among his accomplishments in the War of 1812, according to archive.org, was leading a detachment of Chickasaw Indians against their mortal enemies, the Creeks. Among the warriors in his detachment was Moshulatubbee, the chief of the Northeastern District of the Choctaw Nation (the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians were closely related and both from what is now Mississippi). Below is the name of one of the Privates in his detachment, part of the 39th Infantry.

An example of the Consolidated Military Record showing the name of a Private in Major Blue’s Detachment.

The Tennessee.gov website tells of one of his missions in Florida toward the end of the war (scroll down to Major John Chiles). Blue was under the command of Maj. General Andrew Jackson (yes, the future President of the United States) and led a mission (#20) to storm and capture Spanish Pensacola, Florida. Major Blue was in charge of the Mississippi Militia and the Choctaw Warriors. Jackson had preceded him in Florida, but Maj. Blue’s task was to find the enemy Creeks who had escaped Jackson’ campaign. That particular mission has been considered fairly unsuccessful because Blue’s forces were so poorly supplied.* Another interesting tidbit, though, is that Davey Crockett was with him on that mission.** He then went with his troops to fight with Gen. Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans.

According to the Blue Family research on Major Uriah Blue, he married Rebecca Sturtevant and they had five children. The two youngest ones were still minors when Rebecca died before 1834 and Uriah died in 1836. He is buried in Mobile, AL where he was in charge of an Army garrison at the time of his death.

* See notes about Major John Chiles at http://www.tennessee.gov/tsla/history/military/1812reg.htm.

**http://www.heritech.com/soil/genealogy/potts/bluegen.htm (scroll down to 1.1.3.1.2)

Today, June 18, 2012 is the Bicentennial remembrance of the start of the War of 1812. In honor of this somewhat ignored event, I offer the first of two posts about family members in that war.

Henrietta Munson (1843 -1882) was the wife of Moses I. Woodington. Her great-grandfather (and my 5th great grandfather), Samuel (1739- 1827) was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, serving in the Connecticut militia. According to data from Fold 3, he was a private in the 10th Regiment of Militia in a Company commanded by Isaac Benham.*

Samuel married Susannah Tyler in 1765 and they had seven children. The sixth of their seven children, Freeman (1786 – 1878), joined the Army during the War of 1812. (Freeman was Henrietta’s grandfather and my 4th great grandfather.) According to the U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, (1798 – 1914), Freeman was a Private in the 14th Infantry Regiment in a Company commanded by Captain McDonald. The Army register also notes that he enlisted on January 24, 1814 at the age of 25. He was born in Connecticut, was about 5’11”, and had blue eyes, fair hair, and fair complexion. He signed up for five years, but he only made it five months before he deserted in Albany, NY. He deserted on May 20, 1814.

From the Register of Enlistments (found on Ancestry.com):

Freeman appears again in official records in 1830, living in Trumbull County, Ohio, where he lived the rest of his life. He was there in the U.S. Census’ from 1830 through 1870. It is believed he died at the age of 92 in 1878.

*Fold 3: Connecticut>Ward’s Regiment (1777)>Folder 256>page 4.

In a recent post I spoke of the battle and injuries that landed Lt. John Blue in a Prisoner of War Camp.

He spent some weeks in the military hospital recuperating and then was put into the general population in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C. The Old Capitol Prison building had been the temporary capitol for the United States from 1815 – 1819. The building no longer exists and the grounds now hold the Supreme Court Building. It was not long before he was transferred from Washington D.C., via train, to the POW camp on Johnson Island in Lake Erie, outside of Sandusky City, Ohio. It was here he discovered his cousin, Monroe Blue, was also imprisoned. In Hanging Rock Rebel, by Lt. John Blue and edited by Dan Oates (Burd Street Press, 1994), John Blue described his encounter:

On entering the gate [of Johnson Island POW Camp] the usual warning was given and the echo ran from division to division. “Fresh fish, fresh fish!” this cry brought forth from the door of each room a stream of prisoners anxious to see for themselves if a friend or acquaintance were in the last batch of fresh fish (as every fresh lot was called). I found several acquaintances here whom I did not know were prisoners. The first man I recognized was Monroe Blue, a cousin and a Lieutenant in the 18th Va. Cav. . . . The division in which Monroe Blue was quartered was full, but in the next division a vacant bunk was found of which I was told I could occupy, and my name was placed on the roll of division No.8.

Lt. John Blue described several prison escape attempts—some successful and some not; a few in which he unsuccessfully participated—while on Johnson Island. On February 7, 1864, the prisoners were told there would be a prisoner exchange and that 400 prisoners would be taken in alphabetical order. Monroe and John both determined they would likely go in this exchange because of their last names starting with “B” and, indeed, their names were called. Monroe did not believe that it was really a prisoner exchange. It turns out he was correct—they were being moved to one of the most difficult POW camps in the North at Point Lookout, Maryland. It was in the train ride from Sandusky City, Ohio to Point Lookout, Maryland that the cousins decided to attempt their escape. Here is Lt. John Blue’s portrayal of what became Monroe’s escape:

About 4 p.m. Monroe and I had succeeded in getting seats together. . . . Our plan was to saw a square through the floor of the car large enough for a man to drop through on the outside of the wheels of the car when the engine was taking water at some point east of the Allegheny mountains, where we calculated we would be some time that night. Monroe did the carpenter work while I kept guard. Whenever a Yankee officer entered the car I touched Monroe with my foot, when he would cease work and commence snoring in a frightful manner. When the danger had passed I reached down and gave him a pinch, then he would proceed to business again. In much less time than I had anticipated Monroe pronounced the job complete except about an inch or so at two of the corners, which had been left to hold the floor in place until the time came, when only a moment would be required to remove the square of flooring and the opening would be clear. All things were now ready for us to take our departure, when the time had come. We reached Pittsburgh about midnight, as near as we could tell, where the train stopped until next morning, when we were transferred to another train and did not leave Pittsburgh until sometime in the evening. We were very much disappointed at what we called bad luck, but determined to renew our effort.

The train they were transferred to was set up differently and they were not able to use the same tactic to escape. Winter snows had also been coming down for about twelve hours and John estimated that the snow was 12 – 15 inches deep. He did not have adequate clothing for the cold, but Monroe had recently gotten a package from home that included “a good warm suit of clothes; also a heavy over coat and socks, all home made.” Monroe devised an alternative escape plan in which he would go for a cup of water from the water bucket which was next to the door. Only one prisoner at a time was allowed to go there.

As John continued the story:

I asked Monroe if he thought he could locate the north star. I said keep the star to your back by night and the Allegheny range of mountains on your right by day, in less than 125 miles, if you have good luck you will strike the North Branch somewhere between Cumberland and Green Spring Run.

He said, “I don’t believe in this exchange talk, and I don’t see how I will make my condition much worse;

. . . cut that bell rope if you can.” He pressed my hand a last good bye, arose and walked to the bucket, took the cup from the nail and as he stooped to dip the water placed his left hand on the knob of the car door. As he arose to an upright position threw open the door, stepped to the platform and without an instants hesitation took a flying leap for liberty, not knowing where he would land. The Yankees were quickly on their feet, but the bird had flown. In an instant Monroe Blue had gone from my sight. We never met again.

The rest of the story as John Blue wrote of it is very similar to that reported in my earlier post. John did arrive at Point Lookout, Maryland and then was transferred to a fourth prisoner of war camp at Fort Delaware. He was there when he heard of the end of the war and President Lincoln’s assassination.

David C. Blue (1.1.3.6.1.7 in Blue Family Genealogy) was the seventh of eight children born to Solomon David Blue and Nancy C. (Graham) Blue. His parents had moved to Carmi, White County, Illinois where David was born in 1830. He married Lucinda Ary in 1854 and they had five (or seven?) children. In the 1860 U.S. Census, he and Lucinda were living with two of their young children, David’s sister Alvina, and their father Solomon. David’s occupation was farming.

David enlisted on December 21, 1863 and joined Co. E of the 13th (Consolidated) Illinois Cavalry Regiment on January 20, 1964 with several other men from White County. His regiment spent much of its time in Missouri and Arkansas. The Regiment has been organized early in the war, but had suffered many losses. They reorganized in January 1864 with many new recruits. Prior to his mustering in, the regiment was involved in the Battle of Bayou Forche which immediately led to the capture of Little Rock on September 10, 1863.

The cavalry regiment then moved on and spent several months in or near Pine Bluff, Arkansas. From this location, detachments would set out to other areas for some of their missions.

Private David Blue died at Pine Bluff on June 20, 1864, having served less than six months. He is listed in the regiment’s roll call as one of nine men who died in Pine Bluff in the summer and fall of 1864. Only one man on that roster was listed as “killed” although several “died.” As with most regiments in this war, there were terrifically high numbers of deaths due to disease. The 13th Regiment of the Illinois Cavalry had 21 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded over the course of the war. They lost four officers and 360 men to disease.

In the book by Kenneth Carley, Minnesota in the Civil War: An Illustrated History, the author shares an excerpt from Dr Albert C. Wedge, a surgeon with the Third Minnesota Infantry (p 178):

I come to the memorable summer of 1864 in Pine Bluff, Ark. While there our regiment suffered from a most violent epidemic of malarial fever, and I will only attempt to deal with the causes. In the first place, it is a flat, swampy, unhealthy locality–the Arkansas River on the north and a filthy bayou on the south. The season was dry and hot. The south wind came over the bayou night and day, bringing miasma into our camp. One reason of suffering was the addition to our regiment of a lot of unacclimated men fresh from the North. In April, 1864, several hundred recruits joined us, and were immediately taken into this unhealthy locality. Of these recruits about eight-tenths were stricken down of malarial fever, and eighty-nine died. In June there were added to our number some drafted men. Nearly all fell sick of this disease, and thirty died. It is very unfortunate to be compelled to put men into such an intensely unhealthy locality in the very beginning of their service. We suffered here very much for the want of medical supplies. I could not get a dose of quinine to break the fever on myself. I was relieved from duty August 1st, and went home with the veterans. Had it not been for that circumstance I probably would not be writing this.

Maybe David died in the malaria epidemic. Maybe he suffered from typhoid fever. Another Illinois soldier, Garrett Burkett applied for disability after the war for ongoing consequences from the typhoid pneumonia he suffered while in Pine Bluff, Arkansas in the summer and fall of 1864. In his application for disability it stated, “At Pine Bluff State of Arkansas on or about August or September as now he recollects whilst in camp he was taken sick with typhoid pneumonia in the year 1864.”

Looking at records of regiments from Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, there were many men who died from disease in Pine Bluff, Arkansas in 1864. Whatever the cause, it seems likely that David was among that group of men who died from disease in the terrible living conditions of Pine Bluff, Arkansas in the summer and fall of 1864.