After the 1637 Pequot War, Thomas Munson was given a plot of land to call his own on the plantation and was made a “freeman” in the community. His first land was in Hartford and he stayed there for a little over a year. Sometime in 1639 he sold that plot of land and moved to the New Haven colony. As it was written in The Munson Record, Vol 1:

“Previously to the date of these records, February, 1640, Thomas Munson had quit the Hartford plantation and cast in his lot with the settlers at Quinnipiac. [this blog writer’s note: “Quinnipiac” sounded like and has come to be spelled “Connecticut.”] Such experiments were numerous . The Historical Catalogue of the First Church, Hartford, gives the names of 147 early members ; seventy-four of them, including Thomas Munson, are said to have removed to other settlements. The men who had a sight of Quinnipiac while engaged in the Pequot War, were enthusiastic over the place. (1)

New Haven had been established in 1638 and on 4 Jun 1639, a Fundamental Agreement, the original constitution of the Colony, had been signed by the 63 “free-planters” who had bought the land on that plantation. They decided that any other men who bought land on the plantation would also be expected to sign the Agreement. Soon after the Jun 4 signing, Thomas Munson moved to New Haven and was the sixth signer of the new group who were added after the original signing. (2)

(1) The Munson Record, Vol 1, p 5.

(2) ibid.

(3) ibid. p 61.

Each holiday season for as long as I can remember, my mother has made traditional Christmas Suet Pudding for our Christmas Eve dinner. She uses a recipe handed down for many generations by her ancestors–the Michael Hope family from Darlington, County Durham, England. Yes, it does have real suet in it, but when you have it once a year and share the batch with your family, it does no harm.

Several years ago, Mom and Dad started a recipe book for their children that included lots of recipes we consider family favorites. Our Christmas Suet Pudding recipe was included. Like many English puddings, it is more cake-like than what we think of when we say “pudding” and it is a delicious dessert to finish up a Christmas Eve (or Christmas Day) dinner. Enjoy!

The Hope Family Christmas Suet Pudding

1 cup sugar

2 eggs

1 cup sour milk

1 tsp. baking soda

2 cups flour

1 tsp. cinnamon

1-1/2 tsp. cloves

1 cup raisins

1 cup ground suet

Slightly beat eggs, add sugar slowly, beating as you add.

Sift flour, baking soda, cinnamon, and cloves and add alternately with sour milk. To make your own sour milk, add 1 tablespoon vinegar or lemon juice to 1 cup milk.

Add raisins and suet and stir in.

Place in pan and steam for 3 hours.

Sauce: serve warm with 1 cup sugar, 1 tablespoon flour, mixed, and add water to the right consistency for syrup. Boil. Add vanilla and brandy to taste.

The best suet is the kidney suet—ask the butcher for suet for “people eating”, not for the birds, and he may also grind it for you.

Here is a video clip of the Rite of Confirmation at Salem Lutheran Church on December 9, 2012.

Following are excerpts from an article written by Edgar Aderman (1923 – 2010) in The Aderman Memory Book: Reminiscences from the family of Carl & Floy Aderman.

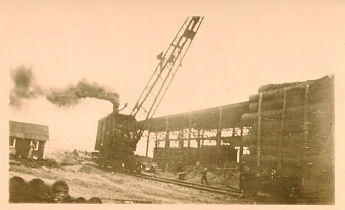

. . . I remember hard work on the farm. Harvesting sugar beets was always a big job. Dad [Carl] had a job as a crane operator at the sugar beet factory in Menominee. As a condition of employment, he had to put in 3-4 acres of sugar beets each year to sell to the company. Dad didn’t do much work putting in the crop; he just told the kids to do it. The seeds were planted in rows. When the sprouts came up you’d have to go through the rows and hoe out a hoes-width between plants. The plants were blocked up. Later on, you’d have to get on your hands and knees and pull out smaller plants and leave the larger ones. A lot of times we didn’t begin to gather them until October and it could get really cold They were pulled from the ground with a lifter (or beet fork) and then the tops were cut off with a knife. Mom [Floy] used to cook the tops to feed to the pigs. The harvest was thrown on a truck and taken to Menominee where carload after carload of beets were washed and processed.

We had three to five pigs and slaughtered two of them each year. Mom canned them, or smoked the hams, bacon, and shoulders. She fried the pork and placed it in big 3-4 gallon crocks. Rendered fat, or lard, was placed over the top to form a seal and the crocks were stored in the root cellar.

The chicken coop housed about fifty birds. Mom used to buy baby chicks of which fifty per cent were roosters. We’d feast on the roosters when they were grown and keep the hens for eggs. . .

Dad kept about eight to ten cows of which about eight were milkers. All of us shared in the milking chores including Mom. Dad sold the milk to the cheese factory. . . . We’d fill two 10-gallon cans a day. For several years Mom would separate the milk and sell the cream. . . .

Pickles were another labor intensive crop that we grew. We’d raise pickles and sell them to the pickle factory at Stephenson. They only wanted a certain length, so we had to check every day for pickles that reached a particular size. We had about one acre and when the pickles were ready we picked every day. . . .

Potatoes were harder to process. The potato cultivator took four horses to pull it. We had a team of horses, Junie and Patty, and our neighbors, the Borski’s, had a team. We’d combine the teams to process each other’s potatoes since each family had about the same acreage.

We also ate dandelions. They were pretty good if you picked the leaves in the spring when they were tender. We would eat them like spinach.

[Edgar concluded:] The kids today would never believe it.

The families of Carl and Floy (Bates) Aderman and Martin, Jr. and Katherine (Storck) Boerner came together in Niagara, WI. Niagara is on the Menominee River which helps create the border between Wisconsin and the upper peninsula of Michigan. Carl and his oldest son, Oscar, worked at the Kimberly Clark paper mill during the winter months and boarded at Martin’s house behind the mill (his wife, Katherine, had died before this). It was here that Oscar met Martin’s daughter, Anna, his wife-to-be. Eventually, they bought the house from Martin and asked him to continue living with them as they raised their family.

Carol D. Miller, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse and a native of northeastern Wisconsin, wrote a book entitled Niagara Falling. In it, she considers the affects of a large company that cares for (even if paternally) a small community, helps it thrive, and then has to leave the community as a result of the massive economic shifts taking place in the 21st century. She begins her book with a good overview of the best of what Kimberly-Clark brought to the village when it built a paper mill there.

The community of Niagara did not exist until Kimberly-Clark took interest in the region. The story goes that in 1889 John Stoveken built a small pulp mill next to what was known as Quinnesec Falls on the Wisconsin side of the Menominee River. The settlement that formed around the mill was merely a lumber company, blacksmith shop and a store. As late as 1897, there were only two frame houses in the area.

. . . Legend has, “On a bitter cold day in the following February [1898] a bobsled load of Neenah executives drove down the river from the railroad and closed the deal.” Quickly, they tore down the small operation that existed and installed power equipment and built a new mill with two new paper machines that produced fifty tons of water-finish wrapping paper per day. . . . They also renamed the town “Niagara,” obviously because of its resemblance to Niagara Falls, New York.

. . . A successful paper mill needed workers, and workers need places to live, so Kimberly-Clark built houses to rent or sell to employees and the town continued to grow. Workers came to Niagara from Europe, via Michigan or other places in Wisconsin. . . . Martin and Katherine Storck Boerner moved from Germany to Kaukana [Wisconsin] so Martin could work at the Badger Paper Mill, but the mill burned, so he and his brother went to Niagara to find work. Martin stayed at the Grand View Hotel. Eventually he brought his family to live in one of the Kimberly-Clark homes built behind the mill. [This is the house written about above.]

. . . In addition to housing, Kimberly-Clark built the Niagara Community Club in 1917. The clubhouse contained a soda fountain, ice cream parlor, pool room, shower and locker rooms, bowling alleys, a gymnasium and theater, a library and other rooms they rented to the Masonic Lodge. . . . Membership in the club cost $2.00 per year. By 1923, the clubhouse had an adjoining outside swimming pool. The motivation for this pool was to prevent drowning deaths caused by children swimming in the Menominee River.

Throughout its tenure as owner of the mill in Niagara, Kimberly-Clark was the backbone of the community. . . .

This came to an end in the 1970s when the current massive economic changes began. Niagara has since struggled as a community, but it enjoyed almost a century of a great economy and employment. It was during this century that Oscar and Anna (Boerner) Aderman raised their sons in Niagara and enjoyed their retirement.

On this day in 1650, my 10th great-grandfather John Munson, died in Rattlesden, Suffolk, England. He was born 14 Oct 1571, the oldest known son of Richard and Margery (Barnes) Munson.

When John was 20 years old, he married Elizabeth Sparke. They were the parents of Captain Thomas Munson.

The gravestone in Brittin Cemetery in Cantrall, Sangamon County, IL for Elizabeth (McNary), wife of John Blue.

The gravestone in Brittin Cemetery in Cantrall, Sangamon County, IL for Elizabeth (McNary), wife of John Blue.

On this day, November 23, in 1849, Elizabeth McNary Blue (my 5th great-grandmother) breathed her last and was laid to rest at the age of 67 years. She was an “early settler” (a person who comes right after the pioneers in order to “settle” a land for use by more people) from childhood until the end of her life, living the adventures of making new homes in wilderness areas and figuring out how to provide shelter for, feed, and raise her eleven children. Her father, John McNary (1752 – 1830) was a veteran of the Revolutionary War and received land in Kentucky in lieu of a salary when the war ended. It was there that Elizabeth and John Blue, Jr. (1777 – 1841) married on 30 April 1801. The couple lived in Kentucky for 20 years before they “moved west” to Ohio sometime between 1821 and 1823. By 1830, they had moved even further west to the newly opened land of Illinois. Something of their lives in Sangamon County, IL was described in an earlier post.

Today is a celebration of a courageous, hard-working, sacrificing woman who gave up many of the comforts of life to contribute to the development of a very young nation.

In the 17th century, just a hundred years after the Reformation had begun, the Church of England which had developed out of the Reformation was still unsettled. Some of its members thought it had not gone far enough and was still too filled with human rules and traditions based in pagan rites. Those members wanted a “purer” faith founded on the Scripture only and became known as “Puritans.” In order to find a place where they could live according to their beliefs and make a good living doing it, many of them moved to North America. It started as the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Plymouth Colony and then expanded to the New Haven Colony.

My 9th great-grandfather, Thomas Munson (1612 – 1685) and his family were among those Puritans who established the New Haven Colony (later to be absorbed into the Connecticut Colony). The Puritans had a defined hierarchy within the community with the upper echelon being “freemen.” When Thomas first moved to the colony, he was neither a freeman nor, on the other end of the white male hierarchy, a hired servant or an indentured servant. (Women and children had no status or rights; there were a few African and Native American slaves, also with no rights, of course.) Through his service in the Pequot War, he earned the status of a freeman. As such, he was allowed to become a member of the church, own property, and vote in community elections. He likely also needed to prove a “conversion experience” to become a member of the congregation (1).

At a “General Court,” June 11th, Thomas Mounson, Francis Newman and four others ” was made freemen and admitted members of the Court.” A list of 70 names, comprising “all the freemen of the Courte of New Haven,” in the handwriting of Thomas Fugill (whose term of office expired 16 March 1646), has Thomas Mounson as No. 25. (2)

The Puritans held themselves and each other to extremely rigid standards of behavior. The penalties for living outside those standards were harsh. They used the stocks and pillory, the ducking stool, wearing letters, and even more extreme punishments. This was not just for the sake of cruelty, but they worked hard to live to a standard they believed would honor their faith and their Lord. They believed passionately in predestination–the theory that only specially chosen people were “predestined” to be accepted in heaven–and were committed to behaving in ways which they believed would be deserving of that status if they happened to be among the predestined. They also valued education and worked hard to educate their children. Both Harvard (in Boston, MA) and Yale (in New Haven, CT) Universities were begun by the Puritans–Thomas Munson’s descendents being among those who help establish Yale.

As a member of the congregation, Thomas became a person of some esteem. He was among the leaders who wrote to the Rev. Increase Mather asking (after having been turned down after an earlier request) that his son, Cotton Mather, might come to New Haven to be their pastor (3). In part, the letter requested (in 17th century English):

Having formerly made our Address to the Rev. M [Mr] Cotton Mather, a worthy member of your Society, and (for a tyme, limited as we understood, in ministry) among you as an Adjuvant to his hono [honored] father, your Rev Pastor,–hoping at the end of that tyme to have attained him for the supply of our great and pressing necessity. Instead thereof, . . . we found dissappoinmt [disappointment] . . . . Now, although by renewing our mocon to yourselves about that worthy & p-cious [precious] Instrument, . . . yet not knowing what God may doe [do], nor how far the sence of our inexpressibly sorrowfull condicon may affect your harts with a compassinat simpathy with vs [us] therein, and incline you to deny yourselves . . . to helpe a poore church of Christ in eminent daunger of vtter [danger of utter] ruin & desolacon [desolation] . . . we are bold to make this applicacon to your selves.

Signed by William Peck, Thomas Munson, Moses Mansfield, John Cooper, John Winstone. (4)

Joanna (Mew) Munson, Thomas’ wife, would not have had any rights in the community but their son, Samuel, was raised in the faith and became a second-generation leader among the Puritans. The Puritan “experiment” only lasted a few generations, but had lasting effects on the psyche of this country.

(1) http://public.wsu.edu/~campbelld/amlit/purdef.htm

(2) The Munson Record, Vol 1, p. 6.

(3) ibid. pp. 55 – 56.

(4) ibid.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was established in what we now know as New England in 1628 and about 20,000 people migrated there in the 1630s (1). The colony was a dual function as a Puritan religious community and also a business venture. Among those immigrants were The Reverend John Davenport, a fervent Puritan, and Thomas Eaton (2). They had intended to move to Boston but the Boston congregation was in some turmoil, so the men were instrumental in paving the way eastward toward the ocean. Sometime in the 1630s, among the many Puritan immigrants leaving England for religious freedom was my 9th great-grandfather, Thomas Munson (1612 – 1685).

As the Puritans were expanding toward the ocean and the rivers that would support their trade, the native population that was already living on the land were called the Pequot people. There were some attempts in the 1630s to live with the Pequot, but a couple of unfortunate murders that were blamed on the Pequot (rightly or not, it is not known) and the religious passions of the Puritans led to a short, terrible war.

The Puritans believed rather fiercely in the Scriptures and the rights it gave them as a people. By today’s standards of tolerance and respect among faith traditions, their beliefs would be very difficult to accept. But feeling the right and necessity of abolishing the Pequot people, in the midst of a cultural clash, the Puritans attacked at night on May 26, 1637. As it was explained (3):

Captain John Underhill, one of the English commanders, documents the event in his journal, “Newes from America” :

Down fell men, women, and children. Those that ‘scaped us, fell into the hands of the Indians that were in the rear of us. Not above five of them ‘scaped out of our hands. Our Indians came us and greatly admired the manner of Englishmen’s fight, but cried “Mach it, mach it!” – that is, “It is naught, it is naught, because it is too furious, and slays too many men.” Great and doleful was the bloody sight to the view of young soldiers that never had been in war, to see so many souls lie gasping on the ground, so thick, in some places, that you could hardly pass along.

The massacre at Mystic is over in less than an hour. The battle cuts the heart from the Pequot people and scatters them across what is now southern New England, Long Island, and Upstate New York. Over the next few months, remaining resistors are either tracked down and killed or enslaved. The name “Pequot” is outlawed by the English. The Puritan justification for the action is simply stated by Captain Underhill:

It may be demanded, Why should you be so furious? Should not Christians have more mercy and compassion? Sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents. Sometimes the case alters, but we will not dispute it now. We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings.

It is not known exactly what Thomas Munson’s role was in the war, but he was a Lieutenant in the militia. According to the book, Immigrant Ancestors: A List of 2500 Immigrants to America before 1750, Thomas immigrated in 1637, the same year as the Pequot massacre. Because of his part in the war, he was granted land and the opportunity to be a “freeman”–a man who owned land, was a member of the Puritan church, and could vote in community affairs.

(1) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massachusetts_Bay_Colony

(2) http://www.colonialwarsct.org/1638_new_haven.htm

(3) http://www.pequotwar.com/history.html