Lt. John Monroe Blue (1834 – 1903) was the son of Garrett I. Blue (1.1.1.1.10) and the grandson of Revolutionary War soldier, Captain John Blue (1.1.1.1. in Blue Family Genealogy). His grandfather had moved to Hampshire County, Virginia with his parents, probably in 1752. While many of the children and grandchildren of his Grandfather Blue had moved further west to Ohio and Illinois, Garrett I. and his son, John, stayed in Hampshire County.

A (very) brief history of Hampshire County at the start of the Civil War was included in the recent post about Monroe Blue, a great-grandson of Captain John Blue. Lt. John Blue served in the Confederate Army serving in Company D of the 11th Virginia Cavalry. He kept diaries of his war experiences and those became the basis of a series of articles he wrote in The Hampshire Review from 1898 to 1901. Those articles were collected and edited by Dan Oates in the book Hanging Rock Rebel: Lt. John Blue’s War in West Virginia & The Shenandoah Valley.

In Chapter XVII of Hanging Rock Rebel, Lt. Blue wrote of the experiences of his last battle. His regiment was sent back to the Shenandoah Valley. There in the Blue Ridge Mountains, near the Rapidan River was where the Battle of Jack’s Shop took place on September 22, 1863 with Maj. General J.E.B. Stuart leading the Confederate troops. He took on the Union’s Brig. General John Buford but the Confederate troops got trapped when the Union Brig. General Kilpatrick showed up and attacked the Confederate troops from the rear.

Here is Lt. Blue’s recounting of his experience:

I imagine every man in the command realized the fact that we were hemmed in between two heavy columns of infantry; in a trap from which, to the ordinary soldier, there seemed no avenue of escape. This trap we well knew would be sprung on us at early dawn, as further concealment would then be impossible.

[The Confederate forces attacked first; the Yankees quickly responded. Blue was sent to relay a message.] . . . I soon found the Colonel and delivered the order. The Colonel at once ordered one squadron of his regiment down through an old field grown up with low pines. I rode along with the Colonel and Adgt. Lieut. Armstead. We went down the hill on a charge firing in the air and yelling like savages not expecting to run on to Yankees, at least I was not. We had gone but a short distance when the boys in blue seemed to spring up as thick as Mullen stalks in an old pasture field, and closed around us. The morning was a very foggy one. When the smoke of battle became mixed with the fog, objects could be seen but a short distance. The Colonel, no doubt, concluded that he had carried out his orders to the letter and that his feint was a success. He turned back after having thrown his revolver in the face of the enemy, of course I could not fight Mead’s whole army, and followed the Colonel. Not over a half dozen mounted men who wore the gray were gathered around the Colonel which was all that could be seen and appeared to be all that was left of the squadron, which it always seemed to me was offered a sacrifice to save the command from capture.

Our revolvers were empty and useless. With the sabre we were making a desperate, though vain effort to extricate ourselves from the living raging sea of blue that surrounded us. It was cut, thrust and parry; parry, thrust and cut. We were slowly carving our way back to the top of the ridge; the horde that surrounded us was much thinner. I now began to hope that some of us would be left to tell the tale. The Colonel and his Adjutant had gone down, three of us were left together. We had nearly reached the brow of the hill when a regiment or brigade only a short distance to our right, which owing to the fog and smoke, had not been seen, gave us a volley, and I was alone, my two comrades went down. . . . We both came to a halt [Blue and his horse which had just been killed], my horse was dead and for some time I was almost as bad off as my horse. Only after a time I came to life again, though memory seemed to have departed. I could not tell where I was, how I came there or what had happened. Right here my experience as a soldier in the field closed, and my experience as a soldier in prison commenced.

Lt. Blue was badly wounded and taken as a prisoner of war. He gradually regained consciousness and realized his situation.

My hair and whiskers were so clotted with blood and dirt that he [the Union soldier caring for him] said he could not tell much about it but that it was in a bad fix and might give some trouble. He then asked if I had been hurt otherwise. I said that I had a bad pain in my back or side. He ordered my Yankee friends to strip me. When my coat had been removed the surgeon looked it over carefully and remarked that if my body had been as well ventilated as my coat I ought not suffer for want of fresh air. He said there was a least a dozen holes in that coat that were not tailor made. After making a hurried examination the surgeon said, “Colonel, you have received pretty bad treatment; you have at least three ribs loose from your back bone; have a bullet in your left knee and have been three times punctured with the bayonet, but your head is by far your most serious hurt.”

He was then ordered to be cared for in a basic way, was put on the ambulance and transported to Old Capitol Prison. There he laid in the hospital ward until he had recovered from his wounds. He spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war.

In June 1861, early in the Civil War, there was a battle for control of the town of Romney in Hampshire County, VA. The north won that fight and claimed an early victory in the war. There is an interesting–and clearly “northern” perspective of the Battle of Romney as published on July 6, 1861 in Harper’s Weekly. The town was then fortified by General Kelley of the North for the time being.

When the Confederate General Stonewall Jackson learned of this, he began a plan to recapture the town of Romney. He needed information on how best to do that so selected three local Confederate soldiers to spy on the town and the countryside surrounding it. Lieutenant John Blue (1.1.1.1.10.3 in the Blue Family Genealogy) of Hampshire County, Major Isaac Parsons, and William Inskeep were appointed by Jackson because they knew the land so well. According to Hu Maxwell and Howard Swisher in their book, History of Hampshire County, West Virginia, from its earliest settlement to the present, published in 1897 and found on Google eBooks:

[Stonewall Jackson] . . . instructed them to secure all the desired information possible by such method as they might think best. They were acquainted with every acre of the country around Romney. They procured a good spyglass, and early one November morning, 1861, took their post on Mill Creek mountain, on the opposite side of the river from Romney, about one and a half miles distant. From that position they had full view of the town, all the surrounding country, the fortifications, the barracks, and everything of a military nature. Isaac Parsons was skillful at drawing, and he and William Inskeep climbed into a tree, made themselves as comfortable as possible, and with the aid of the spyglass, proceeded to make a map of the military camp, with all the converging roads and the neighboring hills. Lieutenant Blue stood guard at the foot of the tree, on the lookout for objects nearer at hand. It was a warm day, although in November, and it was nearly sunset when the map was finished, and the men were ready to come down from the tree. About that time the soldiers in Romney were called out on dress parade, and the spies had excellent opportunity of estimating their number, and they remained in the tree a short time longer for that purpose.

In the meantime Mr. Blue’s ear had detected sounds of approaching footsteps, on the mountain side, below them. He called the attention of his companions to the noise, and they descended from the tree, put on their coats, took up their guns, and were about to follow Mr. Blue, who had gone up the mountain and was about forty yards above them, when two federal soldiers made a sharp turn round a clump of tress, and called to the spies to surrender. The soldiers did not see Mr. Blue, nor did they know of his presence. “You are our prisoners,” exclaimed the soldiers as they jumped behind trees to protect themselves from the muskets of the spies. “I am not so sure of it; I guess you are our prisoners,” replied Mr. Parsons. “Not a bit of it,” returned one of the yankees [sic]; “throw up your guns and surrender.” “You throw down your guns and surrender,” said Parsons. It was an even match. All four of the men were behind trees, about forty yards apart. After standing awhile, each side trying to persuade the other to surrender, one of the yankees called out: “Hello, Reb!” “Hello, Yank,” was the reply. “Suppose we shake hands and call it square. We don’t want to hurt you fellows, and I guess you are not thirsting for blood.” Mr. Parsons answered that he was not very blood-thirsty and was willing to let bygones be bygones, and was ready to have peace. “Who are you, anyhow?” inquired one of the the yankees. “Citizens out hunting.” “Well, there is no use to fight over it,” answered the federal, “but that musket you have looks like a rebel’s. How about it?” “The musket is all right, and if you want to shake hands with us, be about it.” “Leave your gun and step out, and I will leave mine and step out,” suggested the yankee. Both did so; Parsons stepping out first, then one of the federals. Then Inskeep stepped out unarmed, and called on the remaining yankee to do likewise. But the treacherous child of the frozen north sprang out with his musket leveled and called out: “Now surrender. I have the drop on you!” “Drop that gun,” came a command from the hill above. Lieutenant Blue had stepped from behind a tree with his gun leveled at the yankees. The table was turned. The yankee dropped his gun and began to beg. He said he was only joking and had no intention of shooting anybody. “I am not joking,” replied Mr. Blue, “and if you want to save your hide, leave your gun where it is and strike a trot for Romney and don’t dare look back until you get out of sight.” The yankee did not stand on the order of going, but took to his heels. The other yankee was told to leave his gun and follow his comrade. He did so.

That night, the spies stayed at the home of an acquaintance and then continued their work from a different location, watching the Northern troops search for them in the woods around Mill Creek mountain where they had been the previous day. They finished their work that day and then continued on to Blue’s Gap, sending the map they had made to Stonewall Jackson.

Lt. Blue’s story did not end there. More to follow . . .

The last blog told about Abner Blue and his work with the Underground Railroad, helping escaping slaves pass from northern Indiana into southern Michigan on their way to Canada. Today’s post is about one of Abner’s distant cousins, Monroe Blue, and his experience as a Confederate soldier.

At the start of the Civil War, the people of Virginia were split about whether or not to secede from the Union. The state was also split geographically by the Allegheny Mountains. Generally speaking, the people west of the Allegheny range wanted to stay with the North and the people east of the mountains voted to secede. This led the counties in the west to vote to create their own state named West Virginia. The state was admitted into the Union in 1863. Hampshire County, even though it was right on the eastern boundary of the Alleghenies, voted to go with West Virginia.

In the eBook, “History of Hampshire County, West Virginia, from its earliest settlement to the present” by Hu Maxwell and Howard Llewellyn Swisher, 1897; found on Google eBooks, the authors wrote, “It should not be understood, however, that there was no sympathy with the south in this state [the newly formed state of West Virginia]. As nearly as can be estimated, the number who took sides with the south, in proportion to those who upheld the union, was as one to six. The people generally were left to choose. Efforts were made at the same time to raise soldiers for the south and for the north, and those who did not want to go one way were at liberty to go the other. In the eastern part of the state [of West Virginia, where Hampshire County is] considerable success was met in enlisting volunteers for the confederacy; but in the western counties there were hardly any who went south.” (p. 159)

John Lawson Blue and Eliza Blue Monroe were born in Hampshire County, Virginia and lived there throughout their lives. When West Virginia split off from Virginia during the Civil War some of the Blue family living in Hampshire County fought for the South. Their son, Monroe, fought for the Confederacy. Monroe was born in 1841 and died in 1864 as a result of the war.

He originally served in Company A of the 33rd Virginia Infantry and later was part of the 18th Virginia Cavalry. In History of Hampshire County, there is quite a detailed report of Monroe’s experiences as a soldier:

Death of Monroe Blue

The escape from prison and the subsequent death in battle of Lieutenant Monroe Blue have been already spoke of in the history of the company to which he belonged; but the subject demands a more extended notice, as he was one of the bravest soldiers Hampshire sent into the field. Lieutenant Blue was one of a party of confederate prisoners who were confined at Johnson’s Island, in the state of New York. After being in prison ten months, the order came to remove them to Fort Delaware, a prison near Philadelphia. For a long time Lieutenant Blue had meditated escape, but the opportunity did not come while at Johnson’s Island. When placed on the train for the trip to Fort Delaware he undertook to cut a hole through the bottom of the car. He had hacked the edge of his pocket knife and had converted it into a saw. He was making good progress toward cutting through when the guard discovered him, and his plan was frustrated. He then resorted to the more desperate expedient of knocking down the sentinel on the platform and jumping off. The bell rope was cut by some one at the same time, and the signal to stop the train could not be given. The leap from the cars somewhat injured his side and hip, falling as he did upon the rails of the double track at that point. But in the excitement of the moment, and in his eagerness to see his native hills, he forgot his injuries. He fortunately escaped being shot, although the sentinel on the next platform fired at him at close range. The Yankee whom he had knocked down could not regain his feet in time to fire; and the train could not be stopped. He, therefore, made his escape for the present. This occurred at a point in Pennsylvania about seventy miles west of Harrisburg. After getting free from the train guard, he still had dangers innumerable and hardships appalling ahead of him. The stoutest heart might have yielded to despair. He was in the enemy’s country, and every man’s hand was against him. He was without money. It was in the dead of winter. If he remained in the woods he was in danger of starving and freezing. If he ventured to houses for food he was liable to arrest. He set forward in a southerly direction, and traveled days and nights, by field, wood, road, path, and wilderness. Four times in the four days hunger drove him to houses for food. He passed himself as a railroad hand and was kindly received. When he slept an hour or two occasionally from sheer exhaustion, he wrapped himself in his overcoat and lay upon the frozen ground. When he was obliged to pass a town he usually did so at night; but he walked through Bedford in the day time. In four days and nights he walked one hundred and fifty miles, and finally reached his home in Hampshire county. His relatives were taken by surprise. They had supposed him dead.

Detachments of federal troops at that time were overrunning Hampshire. Among them was Averell, with his cavalry, passing through on one of that general’s accustomed dashing movements. Although Lieutenant Blue was weary and footsore, he did not hesitate to do all he could to retard the progress of the Yankee general. He succeeded in blockading a point on Averell’s line of march so securely that rocks had to be blasted before the union troops got through. Lieutenant Blue soon joined his regiment, and on June 5, 1864, took part in the battle of New Hope, in Augusta county. At the commencement of the fight some of the dismounted officers of the brigade were ordered to take command of the dismounted men and deploy them as skirmishers, but they all seemed slow in obeying the command. Lieutenant Blue sprang from his horse and said he would lead the dismounted men. He thus entered the battle, but never returned. As he was leading his men he was shot through the neck and fell dead. On that day died as brave a soldier as ever gave up his life on the field of battle.

More about this battle, the Battle of Piedmont, can be found here.

Abner Blue (1.1.2.1.1.9 in the Blue Family Genealogy) was born in Troy, Miami County, Ohio in 1819. His father, James, was a Justice of the Peace in Troy, an associate judge, and represented Miami County in the Ohio State Legislature. He died the same year Abner was born. Abner was the youngest of their nine children and he moved with his mother to Elkhart County, Indiana when he was 17. This was in 1836-37 and the politics of slavery were heating up. Indiana in its earliest configuration was part of Virginia and did have slavery. By the time Abner moved there, Indiana had became its own state and, while they were not welcoming to the escaped slaves or freed Blacks, they did not allow slavery within the state borders.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, many churches in the state took strong stands against slavery; other abolitionists took a constitutional angle, asserting it was contrary to the Constitution of the United States. A more radical group held their beliefs quite passionately and acted on them more overtly. Abner Blue was among them. “There is a law above all the enactments of human codes,” one Hoosier wrote; “it is written by the finger of God on the heart of man, and by that law, infinite and eternal, man can not hold property in man.” This group was willing to act on their beliefs in both legal and illegal ways. The Underground Railroad was one of the illegal ways.

The Underground Railroad had various paths from the South, through the border states, then  through the northern states to Canada. Abner Blue was a key participant in the Underground Railroad in Elkhart County in northern IN (see map).

through the northern states to Canada. Abner Blue was a key participant in the Underground Railroad in Elkhart County in northern IN (see map).

He and some of his neighbors were acknowledged as “conductors” by the Indiana Historical Bureau:

Eliza Harris, the slave mother immortalized by Harriet Beecher Stowe, reportedly stayed overnight at a station near Pennville in Jay County. Conductors also transported fugitives through Silver Lake, Goshen, and Bristol. Jesse Adams, Abner Blue, B. F. Cathcart, William Martin, and C. L. Murray acted as station keepers and conductors on the Bristol Road. The Murray home was the last stop in Indiana, only four miles from Michigan.

Richard Dean Taylor wrote on his website, Slavery in Indiana, “The residence of Mr. Blue was on the Goshen and Bristol road, the first house north of the line between Elkhart and Jefferson townships and in the corner where the roads make its first jog to the east. ” Abner and the other men were successful farmers in the community and quite respected. That, no doubt, helped them accomplish greater successes in their secretive work with the escaping slaves.

The Abner Blue home would have been known as a “station” on the Underground Railroad. They moved fleeing slaves, the “passengers”, from one location to the next, usually at night. There were three main routes through Indiana: west, central, and east. The Blue home was at the very north end of the eastern route, just miles from the Michigan border.

There are many stories of slave hunters chasing slaves in the communities where the slaves were being hidden and transported. If the slaves were caught, they often suffered great cruelties on the way back to their owners and then were punished again when they arrived back at the place from which they had escaped. With the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, anyone caught harboring the escaping slaves could be arrested and punished accordingly. Thus, the need for secrecy was created.

The conductors on the railroad agreed to provide food, clothing, and shelter as they were able for the runaway slaves. When they determined it was safe, they moved them to the next location on the railroad. Abner was married to Harriet Clay in 1848 until her death in 1859. They had five children. Then he married Eliza Doolittle in 1862 and they had two children, although the oldest of those was born late in the Civil War (1864) and the younger one was born in 1874. Presumably, the children would not have known of their father’s participation in the Underground Railroad because the risk was awfully high if they told anyone; it is unknown if the wives knew. It is known that he hid the slaves on his farm, but there would have been many, many hiding spots from which to choose.

Abner lived until 1894 and died in nearby Goshen, IN.

*****************

October 5, 2013

As a follow-up to this post, Joan Stiver commented on this article with the following insights. Her book can be found on Amazon as both a paperback and a Kindle download. It is a great read. I highly recommend it! CJ

From Joan:

What a wonderful site! We lived on S. R. 15 in Jefferson Township north of Goshen from 1980 to 1990 when our children were small. At that time we never knew that one of the Freedom Trails was right out in front of our house. As a second grade teacher in the Middlebury Community Schools of which Jefferson Township was a part, we three 2nd grade teachers taught a large unit on the Under ground Railroad especially as it went right through our school district. After I retired I wrote a book for young children about Abner Blue – fiction but based on fact. A few of us interested in this part of history including the Elkhart County Historical Society visited the brick house – probably built in the 1880′s or 1890′s – which still stands today on the old S. R. 15 route. We saw Abner Blue’s name on the deed as the first owner. We learned that his son – in – law owned (or worked at) a brick factory not far away. We know that Abner Blue was a joiner, and we wonder if the beautiful wooden staircase in the home was built by him. The present owners of the house have adopted two black boys from Ethiopia so, in a sense, history has come full circle. Black people now are living on the property where black people used to have to risk their lives for freedom. Joan Trindle Stiver

The Memorial Day celebration that is practiced today has its origins immediately following the Civil War. General John Logan proclaimed May 30, 1868 as a day to decorate the graves of soldiers, Union and Confederate, at Arlington National Cemetery. Here is a good general history of the holiday online. With the nation preparing to celebrate this great remembrance at the end of the month, I thought I would focus on some stories of our ancestors involved in the Civil War, from both the North and South.

Earlier, I wrote of Moses Woodington’s experiences in the Civil War. This month, the stories will come from the Aderman side of the family via Floy Bates, my great-grandmother and the wife of Carl Aderman. Floy is a descendent of the Blue Family and the stories this month will be from the Blue clan.

William Marshall Blue (1.1.3.2.1.8, section 6AX in the Blue Family Genealogy website.) was the son of John and Elizabeth Blue and a brother of Martha Blue who was Floy (Bates) Aderman’s great-grandmother. Born in 1821, “Marsh” left his farm and family to sign up to serve in the Civil War with the 114th Regiment of the Illinois Infantry, a regiment from Sangamon, Menard, and Cass counties in Illinois. This regiment organized at Camp Butler, IL and mustered in on September 18, 1862. They served primarily under Generals Grant and Sherman and fought throughout the South.

William Blue’s Regiment was involved in General Grant’s Central Mississippi Campaign. They were in the “Tallahatchie March” to Mississippi from November 26-December 12, 1862. After that, they did a variety of tasks–guard duty for the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, participating in the Siege of Vicksburg and the assault on that city, and in June of 1864, marched from Tennessee to northeastern Mississippi near the town of Guntown.

In early June of 1864, the highly skilled Confederate Cavalry under the command of Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest started toward Middle Tennessee to destroy the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. The railroad was transporting supplies and men to the Union’s Maj. Gen. William Sherman in Georgia, whose goal was to bisect the South from Chattanooga to the Atlantic Ocean. Concerned about the possibility of Forrest taking out the railroad, Sherman sent Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis and 8100 troops from Memphis to northern Mississippi, hoping that it would redirect the Confederate troops and keep them from destroying the railroad. The strategy worked and on June 10, 1864, the Battle of Brices Cross Roads occurred.

Over 11,000 soldiers battled that day and, even though the Confederate Cavalry and reinforcements were far out-numbered, they defeated the Union forces. The United States Colored Troops arrived to help the Union forces and as the northern troops retreated, the USCT men provided a series of defensive moves that saved the survivors from likely capture. There were 2610 Union deaths that day–about a third of the northern troops engaged in the battle–and William Marshall Blue was one of them. He left his widow, Adeline, and five children.

Part 1 told of the general experiences of the first European-American pioneers in what we now know as Sangamon County, Illinois. It took a special breed of people to venture out into the unknown land and find ways to survive in the unfamiliar, unspoiled land. The early settlers were the ones who eventually followed the pioneers into the territory and helped (as settlers would) settle the land.

Our ancestors Robert (1784 – 1840) and Ann (McNary) Blue (1786 – 1820) and his brother John (1777 – 1841) and his wife [and Ann’s sister] Elizabeth (McNary) Blue (1782 – 1849) and their children were among the first settlers to this central Illinois county.

John C. and Sarah A. Power in their book, History of the early settlers of Sangamon County, Illinois: “centennial record” (published January 1876 by Edwin A. Wilson & Co., found on Google eBooks), shared a bit of the history of the John Blue family as among those early settlers. Here is the bio of the Blues found in that book (I have typed it exactly as it is found in the book; what look like typing mistakes simply represent how the language has changed over the last 130+ years):

BLUE, JOHN, was born Sept 9, 1777, in South Carolina. His father was a soldier in the Revolutionary army, and was taken prisoner by the British the very day of his birth. His parents moved to Fleming county, KY., when he was quite young. Elizabeth McNary was born in South Carolina, and taken by her parents to Fleming county, KY., also. They were there married about 1806, had seven children in that county, and then moved to Hopkins county, where they had four children. About 1823 they moved to Green county, O., [Ohio] where they had two children, and then moved to Sangamon county, arriving in the fall of 1830, in what is now Clear Lake township.

MARTHA married Robert Blue, had six children and died.

SAMUEL married Isabel Webb, had eight children, and resides in Missouri.

DAVID H., born Sept. 23 1816, in Fleming county, KY., married in Sangamon county May 19, 1844, to Fannie Webb, They had two children, one of whom died young. MELISA C. married Abel P. Bice. David H. Blue resides two miles north of Barclay.

ELIZA married Adolphus Jones, had one child and all died.

WILLIAM M. born in Fleming county, KY., married in Sangamon county to Adaline Cline. They had five children. JAMES H. married Catharine Dunlap, had one child DORA E., and live in Fancy creek township. GEORGE W., LUCY, DAVID and PARTHENIA, live with their mother. William M. Blue enlisted in Aug., 1862, in Co. C, 114 Ill. Inf. for three years. He was killed at the battle of Guntown, Miss., June 10, 1864. His widow married M. Hardman, and lives near Cantrall.

HARRISON married Margaret Alexander. They had three children, and he died in Fancy creek township.

CAROLINE married Stephen Cantrall. They have six children, and live near Kansas City, MO.

AMOS went to Oregon when a young man, and resides in Jackson county.

John Blue died in 1842, and his widow in 1848, both in Sangamon county.

The Blue family had been early settlers in Kentucky, arriving there with a land grant after the Revolutionary War (the new federal government had lots of land but not much cash so paid many of their soldiers with land after the war). Moving west to Ohio, they settled in new territory again. The final move for John and Elizabeth (McNary) Blue was to Sangamon County, Illinois. Here they set about the work of domesticating the land so that more people could come and make good lives. The Hon. Milton Hay, continuing his speech at the 12th Annual reunion of the Sangamon County Old Settlers described the early settlers’ task this way:

In process of time came a class who desired progress in improvements and civilizations, and these men began the work. Not content with building for themselves the cabin to live in, they built the early log school houses and churches. They began the work of cultivating the soil for something more than their own personal wants; of opening farms and laying out roads. Then began the location of trading points and towns, and traders and mechanics came in to supply the wants of population. And so, step by step, population and improvement slowly increased. . . . Our trading was mostly a system of barter; an exchange of one article of produce for another; of corn for cattle, or cattle for horses, and of the produce of the farm for labor, manufactures or merchandise. Money as a medium of exchange was scarcely to be had, and hence but little was used. All this belonged to the period anterior to the introduction of railroads. With the facilities afforded by railroads for reaching quickly the great markets, came cash buyers and ready sales. These iron rails not only connected us with the commercial world, but along them came the quickened pulsations of a more commercial life. This quick and ready intercourse with the commercial world, soon affected our old habits and usages, our fashions and modes of doing business. We set about to adapt ourselves to a changed condition of affairs.”

I have been enjoying some of the great old history books found on Google’s eBooks. My interests, of course, tend toward histories of some of the locations where our ancestors lived. It is fun to imagine them living in those times and places. Today’s blog includes an excerpt from History of Sangamon County, Illinois: together with sketches of its cities, villages and townships . . . (published 1881 by Inter-state Publishing Co., found on Google eBooks).

The writing below is from an oration given by Hon. Milton Hay at the 12th annual reunion of the Sangamon County “Old Settlers.” He described the lifestyle of the first pioneers and the early settlers.

Let’s first consider the lifestyle of the pioneers:

In this comparatively early history of the society, however, we had the advantage of having amongst us as yet, so that we meet them, face to face, a few of the very earliest pioneers; men and women who had stood, as it were, upon Mount Pisgah [the mountain top from which Moses viewed the Promised Land], and gazed upon the trackless prairies and forests of these regions; men who saw that the land was fair and who were the first to enter upon it and take possession. The experience of these old settlers was an experience that no other generation of settlers could possibly have. At that early day these regions were not considered so inviting as to cause any rush or haste in their settlement. A few located doubtingly and cautiously, and these at considerable intervals of time. It was no part of the expectation of these pioneers that they would realize suddenly great wealth or great success of any kind by being the first upon the ground. But little information had been disseminated as to the character of the country, but there was a general impression that its characteristics were those of a desert.

There was doubt and question then as to whether a prairie country was inhabitable. The means and modes of access to the country were slow and difficult, and only those were tempted to come who were already frontier men, or who for some exceptional reason preferred the free life of a wilderness to the comforts of the older settled parts of the country. There was at that day no rushing tide of emigration from all parts of the world. There were no speculators, land grant railroad companies, and newspapers engaged in ‘whooping up’ the country. There were many discomforts and deprivations which the early settler had to undergo; but there were compensations also. The early settler was almost ‘monarch of all he surveyed.’ He could enjoy the great natural beauty of the primitive scenery of the country, before it was broken and profaned by roads, buildings and fences. He had no disagreeable neighbors to fret or annoy him. With his gun and faithful dog for company, and the wild game all around him, he cared nothing for the society of men. Of course only a class of men who had long habituated themselves to a life on the outer borders of civilization could enjoy such a life in its full perfection.

I suppose each generation gets to determine its own bounds of appropriateness and humor. As we look over the decades, we can see what some of those are. I smiled at these pictures of Ethel (Woodington) Hope and, at a different place and time, her father-in-law, Michael Hope, Jr. The caption in the photo album under Ethel reads, “Oh my!” These were hilarious and maybe even a bit sassy or outrageous poses a century ago.

Next month we are celebrating the 45th anniversary of the Shell Lake Arts Center. Dad founded it in the 1960s and kept it flourishing for almost 30 years before his retirement. Over the years, the Arts Center has welcomed students from 49 states and six continents. Its tagline is “Master Teachers. Magic Setting.” Both are true and are part of his legacy.

A few days ago, I had the fun of sitting down with him to write for the Boy Scouts of America a brief synopsis of his life since being awarded his Eagle Scout at the age of 16. The intelligence, attention to detail, and focus which helped him accomplish so much in his professional life were still evident as he edited my work. Here are some of my favorite pictures of his childhood in northeastern Wisconsin. Below the picture is the article he helped me write.

ODA earned his Eagle Scout in 1947 plus the bronze, gold, and silver palms and Order of the Arrow. The leadership skills and self-discipline he learned in scouting have served him throughout his life. As a music major at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he played tuba in the marching band, was the band president his senior year, and president of the music fraternity Phi Mu Alpha.

He began his career as a music educator in Shell Lake, WI and soon started the Explorer Scouts in the community, staying active in scouting. He participated in local and state professional organizations and served in leadership positions in many of them. In the 1960s he had a vision for a summer arts program in northwest Wisconsin and worked to create one sponsored by the University of Wisconsin. The Shell Lake Arts Center opened its doors in 1968 and is now the longest running jazz summer program in the nation. ODA was its founder and the director for 28 years and became a professor with UW-Extension. He retired as Professor Emeritus and his work was recognized by Extension when he received the Award of Excellence in 1996. He was honored with the Distinguished Service Award of the Wisconsin Music Educator Association in 1997 and the Distinguished Service Award of the International Association of Jazz Educators in 2003.

He joined the Masonic Lodge soon after moving to Shell Lake and was an active leader in the organization, becoming Grand Master of the State of Wisconsin in 1984 and a Scottish Rite 33º. He was recognized with the Grand Lodge Meritorious Service Award in 1997. ODA credits his training as an Eagle Scout for helping him develop the skills needed for his successes.

The United States had war-time draft registrations in its history (e.g., Moses Woodington and his brother were drafted into the Civil War) but on July 1, 1940, Congress passed by one vote the first Selective Service and Training Act in a peacetime era. President Roosevelt signed the Act into law on September 16, 1940 recognizing the rising level of conflict in the world. The following year, on December 8, 1941, we entered into World War II.

There were six draft registrations during WW II and the fourth of those was called “The Old Man’s Registration” or “The Old Man’s Draft” because it required men between the ages of 45 and 64 years to register. This registration was held on April 27, 1942 and mandated that men born “on or after April 28, 1877 and on or before February 16, 1897” fill out a registration card.

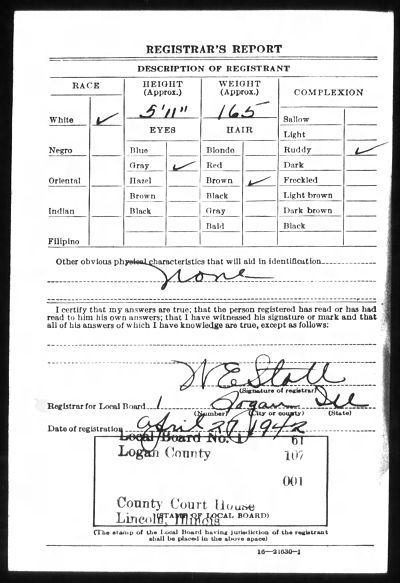

Below is the registration card for Ferdinand and Mary’s son, Theodore “Tad” Rudolph Aderman. His wife, Cleva, is recognized as the one “who will always know your address.” We also get a bit of a physical description of Tad at the age of 47.

A great-grandson of Ferdinand and Mary Adermann died on Sunday, December 18, 2011. He was the son of Vera (DeJong) Cavenaile (1921 – 2005) and the biological grandson of Mary Adermann Krumreich (1892 – 1921). His grandmother, Mary, died at the age of 28 giving birth to Vera. Vera was then raised by Mary’s sister, Ernestena (“Tiny”) Adermann DeJong (1890 – 1960)–hence Vera’s last name in the following obituary.

Here is a remembrance of Ron:

Ronald R. “Cav” “The Man” Cavenaile, age 60, of Plainfield, passed away suddenly, Sunday, December 18, 2011.

Ronald R. “Cav” “The Man” Cavenaile, age 60, of Plainfield, passed away suddenly, Sunday, December 18, 2011.

Born May 4, 1951 in Springfield to the late Alexander and Vera (nee DeJong) Cavenaile, he was a graduate of South East High School in Springfield, IL. He moved to Joliet in October 1977. He retired January 2006 from AT&T after 33 years of service as a customer service technician.

He leaves his dear wife of 40 years, Chris (nee Stokes) Cavenaile; his beloved children Paul (Melissa), Kevin (Stephanie) and Scott (Jill) Cavenaile; the grandchildren he loved and was devoted to: Ethan, Olivia, and Abigail; Carter, Coleman, Carli and Caden; his sister, Marie Cavenaile of Springfield, IL; and many nieces and nephews who survive him.

Ron was preceded in death by his parents, Vera and Alex, and two brothers, Alex and Thomas.

He was an avid outdoorsman, who enjoyed hunting and fishing. Ron was a great mentor to his sons; he could fix just about anything. He loved being with his family, whether it was dinner with his wife, playing with the grandkids, or educating his sons in the “Club Cav” (Ron’s garage), time with Ron was always memorable.

Funeral Services for Ronald R. Cavenaile were held Thursday, December 22, 2011 at 10:00 a.m. at the funeral home with Pastor Bob Hahn officiating. Interment was at Plainfield Township Cemetery. In lieu of flowers, memorials in his name to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital would be appreciated.

Fred C. Dames Funeral Home, 3200 Black at Essington Rds., Joliet.

For information: 815-741-5500 www.fredcdames.com

A little introductory information was offered in a previous post about the Donners leaving Sangamon County, Illinois to emigrate to California. James Reed had organized a wagon train of families from the Springfield area who wanted to move to the west coast. He was spurred on by reading of a shortcut through the Great Basin and by much conversation that was sweeping the nation at the time. California was still owned by Mexico, but would soon be a territory of the U.S.

The original wagon train left in mid-April, 1846. By the end of June, they had arrived at Fort Laramie, a travel oasis of sorts, in what we now know as the state of Wyoming. At least two significant events happened at this stop. First, James Reed met a friend of his there who had just taken the “shortcut” and strongly encouraged Reed to not take it–a recommendation Reed ignored. The path was barely passable and would be terrible with wagons. Second, Landsford Hastings, the author of the book recommending the “shortcut” had left a message at Fort Laramie for emigrants that he would meet up with them at Fort Bridger (also in present-day Wyoming) and take them through the pass.

The wagon train journeyed forward and when they arrived at Little Sandy River (Wyoming) in mid-July the party split into two factions. There were two trails to take and most of the participants chose to take the better known and safer trail, even though it would be a longer path. A minority chose to stay with the Hastings shortcut; that group elected George Donner to be their new leader.

As they continued traveling that summer and early autumn, the group of emigrants being led by George Donner had ongoing difficulties. The journey through the Wasatch Mountains took much longer than they had anticipated; the trek through the Great Salt Lake Desert was fraught with obstacles which left their food and water supply dangerously low. They also lost a couple of wagons in the difficult crossing. Recognizing their plight, they sent two young men ahead to buy supplies and bring them back to the wagon train.

The party continued to travel through the autumn but with the strain of the journey taking its toll on the people. One of the tragic accidents along the way was when a wagon axle broke on one of the Donner wagons. While repairing it, George Donner seriously injured his hand–an injury which ultimately led to his death in the mountains and separated the family from the rest of the group. As Eliza P. Donner Houghton (daughter of George) described it in her book, The Expedition of the Donner Party and its Tragic Fate:

Uncle was giving the finishing touches to the axle, when the chisel he was using slipped from his grasp, and its keen edge struck and made a serious wound across the back of father’s right hand which was steadying the timber. The crippled hand was carefully dressed, and to quiet uncle’s fears and discomfort, father made light of the accident, declaring that they had weightier matters for consideration than cuts and bruises (from Chpt 6).

. . . Father’s hand became worse. The swelling and inflammation extending up the arm to the shoulder produced suffering which he could not conceal. Each day that we had a fire, I watched mother sitting by his side, with a basin of warm water upon her lap, laving the wounded and inflamed parts very tenderly, with a strip of frayed linen wrapped around a little stick. I remember well the look of comfort that swept over his worn features as she laid the soothed arm back into place. (from Chpt 8)

Because of this accident, the George and Jacob Donner families and their help stayed behind while the other kept moving forward toward a location that had a cabin. When the early winter snow storm stopped all forward movement, the Donners were still about six miles behind the others and had to build makeshift tents of the blankets they had with them. As the storms got worse, it became clear everyone would be stranded in the mountain snow without adequate food and shelter.

In Part 1, I shared some resources for reading more about the Donner Party Tragedy and explained the Donner Family relationship to our family tree. Now, let’s go back to the beginning of the journey in Sangamon County, Illinois.

George Donner was born soon after the Revolutionary War, his father having fought for the new nation in that war. He had lived in North Carolina, Kentucky, Illinois, Texas, then back to Illinois where he accumulated wealth and land as a farmer in Sangamon County. He and his brother, Jacob, decided to join the company which had formed in the Springfield area to emigrate to California. As George’s daughter, Eliza P. Donner Houghton, wrote in her 1911 book, The Expedition of the Donner Party and its Tragic Fate”

Mr. James F. Reed, a well-known resident of Springfield, was among those who urged the formation of a company to go directly from Sangamon County to California. Intense interest was manifested; and had it not been for the widespread financial depression of that year, a large number would have gone from that vicinity. The great cost of equipment, however, kept back many who desired to make the long journey.

James Reed was the leader of the wagon train when it left. According to the Legends of America story of the Donner Party, Reed had read a book by Landsford Hastings, The Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California, which told of a shortcut across the Great Basin which would eliminate as much as 400 miles from the trip. As it turns out, it seems Mr. Hastings had never actually taken the journey to know if it really worked and in an ironic twist, left California to test out the shortcut on the same day the Reed/Donner wagon train left Illinois.

On April 15 or 16, 1846, the Donners said good-bye to their grown children who stayed behind in Sangamon County and left with the younger children for their last great adventure. With several other families in addition to the Reed and Donner families, the nine wagons began their journey. Along the way they had experiences with Indian attacks, murder and intrigue from with the group, changes of leadership among the party, delays, and several changes of who was traveling with the convoy at any given time. With all that happened, what had been anticipated to be a four-month expedition turned into a ten-month trial.

Here is a map from The Donner Party Diaries showing their path:

The Journey of the Donner Party to California (Source: The Donner Party Diaries)

The story continues here.

My genealogy buddy and cousin, Kevin, keeper of Our Family Genealogies, sent me a recipe this week which his grandmother made each Thanksgiving and Christmas. She passed the tradition down to his mother. They reported it had been given to them from Mary (Heiden) Adermann, his great-grandmother. He is now the fourth generation (at least) in his family to be responsible for the annual green and red Christmas gelatin salad. My family already has plans to make it this holiday season as well–a fun treat that connects us to our ancestors.

The recipe is below. I understand Mary would have used gelatin and lime juice–lime Jell-O was not invented until 1930, ten years before Mary died and several decades after she was an adult woman responsible for Christmas dinners. May you enjoy this part of our family heritage.

Holiday Gelatin Salad

Ingredients:

1 Regular Package of Lime Jell-O

1 C Hot Water

1 C Coffee Cream

4 oz Cream Cheese

1 Can Crushed Pineapple (drained)

Walnuts

Maraschino Cherries

Directions:

Add 1 C Hot Water to Jell-O, Let Cool.

After partially set, beat in Coffee Cream and Cream Cheese.

Add Crushed Pineapple and mix together.

Pour into pan or mold.

Add in Walnuts and Maraschino Cherries to taste.

Top with Maraschino Cherries.

Refrigerate until ready to serve.

Enjoy the salad and celebrate your heritage!